“This was the time in her life,” Ondaatje writes of a young nurse in The English Patient, “that she fell upon books as the only door out of her cell. They became half her world.”

That young nurse, Hanna, is deeply traumatized by her experiences as a WWII nurse in Italy. In a bombed-out villa above Florence, books offer her not just an escape into beauty and a world beyond the war (though those are not trivial gifts) but also a space to quietly reorganize herself after the horrors she has suffered.

To me, too, as an asthmatic child, stuck in a steam tent for days on end, books felt like my only door to a wider world. And that childhood experience shaped my way of being in the world: even after I escaped the steam tent—even today, when I am reasonably healthy—books remain half my world. I live inside them, or through them. Some days, the predicaments of fictional characters loom more vividly in my mind than anything that’s happening to me in the real world.

But there was a time during my late teens and twenties, when books also seemed to offer answers—not like the single correct answer to a math problem but the many insights that slowly coalesce into an attitude towards the world. Part of me thirsted for clear answers to the Big Questions. Another part of me (equally powerful) mistrusted them. Novels didn’t threaten or issue demands; they seemed to provide a place where my two opposing needs could co-exist, where I could grow into a worldview and approach to life.

For me, the novelists that ignited this process were two Russian writers of the nineteenth century, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, who burst into my life like fireworks. Their freethinking experiments with novel-writing and Orthodox Christianity challenged what I’d happily absorbed in my teenage years (Episcopalian thinking, British nineteenth-century novels). I prize them to this day.

Some people I know were too busy raising kids and preparing for a career to sink into the kinds of books that change our lives and our thinking. But many of my word-oriented friends sought out books to help them negotiate the tricky turn into adult independence of life and thought. Last week, in my online class, someone commented that Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance had opened up for her new ways of thinking and living. A guest on our back terrace said that Mann’s Magic Mountain had done similar work for him. My husband seconded that and, later, so did his friend Randy. (Other than cool philosophical debates about liberalism, Magic Mountain moved me not at all. Was it because I was female? Or because the closed world of the sanitorium too closely resembled the steam-tent of my childhood?) I can think of a friend who would no doubt choose Eliot’s Middlemarch—a wise, sad book that she re-reads every year—and her partner would probably choose Spinoza’s philosophy. (Why? Maybe he can tell us.)

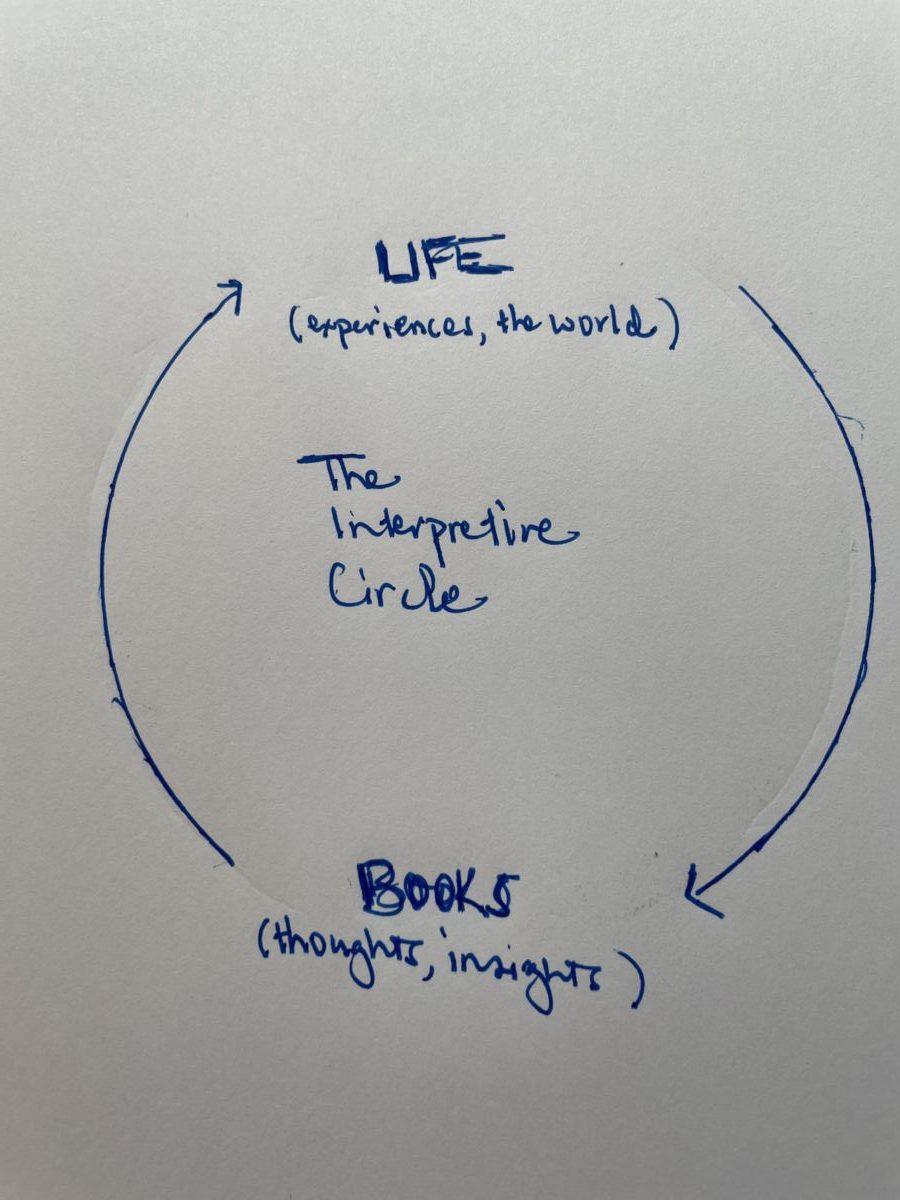

What books set our minds aflame at that age depends a lot, of course, on what issues we need to work out. My friend Jean was sorting out how to balance learning from books and learning from life. Hesse’s Glass Bead Game helped her realize that the two forms of learning might happen not simultaneously but in sequence. (The main character of that fascinating, fantastical novel leaves the world of ideas and art—beautiful but increasingly claustrophobic—to move out into the messy, unpredictable world.) Then Sayers’ Gaudy Night presented her with a picture of how a life/learning balance might work for women–particularly women in relationships. (I, too, swooned over the difficult-to-achieve equality between Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane.)

Issues around gender cropped up for other women, too. Sally mentioned The Mermaid and the Minotaur, a revolutionary analysis of childrearing practices and their long-lasting effects—psychologically, and therefore also socially and politically. (Dinnerstein argued, convincingly in my view, that we all associate childhood with being under the tutelage of women. For both men and women, then, adulthood gets associated with avoiding female control over one’s life. With women still doing most of the childcare, is anyone surprised that it’s taking so long to get women into leadership positions in all walks of life?)

There’s the Big Life Issues, too. People mentioned Gibran’s The Prophet and Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus. I remember my down-to-the-mat struggles with Freud and Nietzsche. Others had their views of science and the universe blown apart by the new work of theoretical physicists.

And you, dear readers? Did you run across books in your teens and twenties that resonated strongly with you? Did books change your ways of thinking or choices in life? Or did life-experiences and conversations do that? And which of those books do you think would hold up if you re-read them?

One of my key books during adolescence was “Franny and Zooey.” For me, it addressed the tension between a deeply spiritual (for lack of a better word) life and the demands of the every day, in a way that made the weaving of these two elements seem rich and possible.

I loved that book, too — and for exactly the same reasons. No wonder we gravitated towards each other….

Hi Nancy. I was never in the position where I had to stay still and read but that activity has always been part of my life. Perhaps because I’m a Gemini by horoscope and a 7 by Enneagram I’m all over the map. I love books with deep mind bending ideas and philosophies mixed in with emotional love stories that tug at the heart strings. The earliest books I remember are from Nancy Drew with her solving puzzles and going on adventures. And while I remember deeply liking Camus, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky I can’t remember much about which stories I liked best but I appreciated how they tackled the BIG topics. And while my own writing never comes close to that I do appreciate them. Nowadays I mainly read nonfiction but now that I think about it, I should take the time to re-read some of those earlier books and let them show me how much i’ve changed…and maybe how much I am the same. Thanks for the thoughts! ~Kathy

I love that “let them show me how much I’ve changed” (or maybe how much you’ve stayed the same)! I’m thinking more and more about re-reading…