Some writer – I wish I could remember his name – tells a story of accompanying an elderly aunt to the hospital in an ambulance. It was night-time, and she noticed dark forms on both sides of the road. “What are they?” she asked. “Trees,” he answered. “Well, I’m tired of them,” she said.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this story now that I’m older. I feel myself getting worn down some evenings towards the end of the day, and in those moment, I can find myself falling into a certain bleakness of outlook. I doubt I’m unusual in this. When toddlers get tired, they get cranky and whiny. Teenagers get sulky and retreat to their rooms. Middle-aged people have a drink and wonder how they’ll get through the rest of the week. We older people do it, too, even if we’re retired. At the end of a tough day, most people are tempted to think, Not only am I feeling down right now, but deep in my heart I’ve always been down. And it’s never going to get better. Not really.

It’s okay to be tired after a day (or lifetime) of effort. For those of us without chronic depression, despair is a passing mood, a natural result of having used up one’s emotional/social/logistical batteries. But on a winter evening when no one else is around, we sometimes look back over our lives and see little except folly and waste: ridiculous and unrequited passions, acts of cruelty and selfishness (by us and by others), and pointless dreams that never went anywhere.

The mood usually evaporates if the sun is shining the next morning. But Erik and Joan Erikson identified a deeper and darker version of this despair as the primary threat of the years beyond the age of 65. (The positive alternative is what they labeled “ego integrity,” the possibility of seeing one’s life as integrated – the bad as part and parcel of the good – and worthwhile.)

That underlying despair is an existential problem, although my psychologist friends would probably note that certain early experiences prime some of us to feel it more strongly than others. Practical solutions abound: it helps for people of any age to discover (or regain) genuine interests (artistic, intellectual, athletic) and to build strong networks of friends and family. When we’re tired, though, it’s easy to globalize our exhaustion into despair and then justify that despair intellectually. It’s easy to lapse into a position that nothing really matters. After all, everyone dies, all human institutions fail, and even the galaxies will eventually collapse in one themselves. When that mood strikes, it helps to have done some philosophical reflection beforehand.

Here are some of my thoughts.

When I was young, I thought that living a good moral/ethical life involved following rules: not telling lies, not betraying trust, not taking things that didn’t belong to one – the whole Ten Commandments thing. I adhered to some amusingly teenagery ones, too, like my fierce belief that one should never, ever steal another’s boyfriend or girlfriend. This obedience-driven way of understanding morality kept me on the straight and narrow most of the time. But the older I got and the more I thought, the more such a position seemed to miss the complexity of actual life decisions. It was too cut-and-dried a theory, too one-size-fits-all.

Gradually I found myself hearkening back to the Greek philosophers I’d read in college, with their emphasis not on rules and perfection but on cultivating one’s moral strengths. The Greek model of ethical life is not a success-or-failure model; it’s a developmental model. It reflects the truth I saw in my students and myself: that no one is born with a fixed, inherent amount of will-power, or courage, or honesty. People learn common sense, resilience, kindness, authenticity. We grow moral muscles as we do our mental and physical muscles, by small exercises of strength. It’s hard and frustrating, and it often hurts, but we practice and get better.

Parts of child-raising acknowledge very clearly that children aren’t born good or bad; yes, they have personalities, but they’re to a large extent morally malleable. Good parents teach their kids to delay gratification, to think of the consequences of their actions, to care about other people, to tell the truth. (Just as importantly, good parents model that behavior.) According to people like Lawrence Kohlberg and Carol Gilligan, who study moral development, most kids engage in what we call black-and-white thinking. They conceive of morality as I did at that age: primarily as a set of rules. This notion of an absolute moral law – whether in its religious form as God-given law or its Kantian form as natural law – is at some level very satisfying. The rules apply equally to everyone everywhere. No one should lie, ever. No one should steal, no matter what the circumstances. It seems logical and fair.

But it doesn’t take long before most adolescents get suspicious of this. No one should steal – ever? Not even if your spouse needs life-giving medicine tonight and you’ve tried to buy it and it’s sitting in that pharmacy window? No one should lie – ever? Not even if the Nazis come to the door and ask if you have Jews hiding in the basement? These are extreme hypotheticals, but ordinary daily life poses similar, if smaller, challenges almost every day.

At this point, thinking about moral life moves out of black-and-white thinking. And here’s where the threat of nihilism arises. It’s an important, complicated moment.

For twenty years of teaching, I watched bright, unhappy teenagers negotiate this dangerous passage to adulthood. As they began to think for themselves, they often oscillated back and forth – partly dependent on their moods – between believing in God-guaranteed moral absolutes and believing in nothing at all. As they realized how big the universe is in comparison with our little dust-speck of earth, the idea of a God who cares about human beings and justice began to seem romantic and unlikely. They tumbled headlong into the simplest and most obvious conclusion: nihilism. And that led to despair, which often manifested itself in a simplistic hedonism. My students – like anyone who has confronted the immensity of the university – often thought, “Screw it. If there’s no purpose to the universe or my life, I’m just going to do what makes me feel good in the moment.” For my students, that often meant a quick descent into reckless, out-of-control behavior – a downward spiral, fueled by despair, that produced self-destructive actions and ended in self-loathing. Simple hedonism just didn’t work. My students had learned that lesson before they arrived at our school. What confused them was this: Is there any other justifiable way to think?

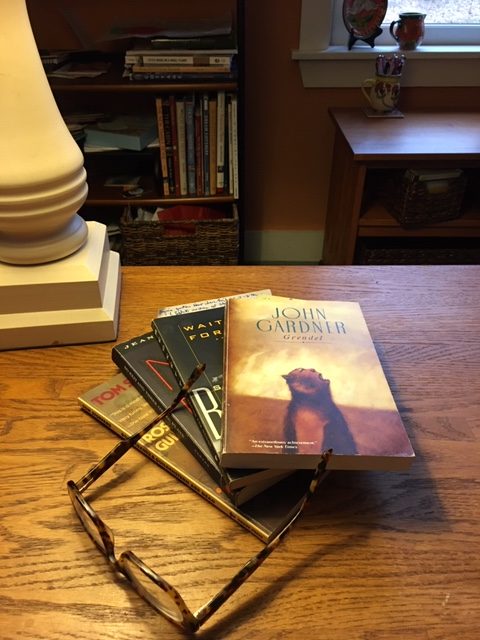

That conundrum is why I loved reading John Gardner’s Grendel with them. In that funny, smart novel, Gardner re-tells the story of the epic Beowulf, but from the monster’s point of view. With snarky bravado , the huge and hairy Grendel tells us that his mother loves him but can’t speak; his uncles are indolent and indifferent to him; he has no one to talk to. When he tries to make friends with humans, they see him only as a terrifying monster and try to kill him. Isolated, despairing, he falls, in a kind of dream, into the cave of a dragon – an apparently omniscient dragon, a cynical anti-God with a dry, malicious sense of humor. For the dragon, all pursuits are futile, all ideals are ridiculous. “Find gold,” he advises, “and sit on it.” Poor Grendel can’t mount any arguments against the dragon. So out of his despair, for his own amusement, he sets out to expose the flaws and absurdities of the ideals held by the humans: poetry, heroism, beauty of the body and soul, social justice, philosophic theology. One by one through the rest of the novel, he exposes them as absurd, ridiculous dreams. It’s cynical and mean and very, very funny.

But even Grendel knows that the real reason he’s destroying human ideals is because he’s bored and lonely. It gives him something to do. It gives him revenge on the humans who despise him; it reduces them to his level. But the brimstone smell of the dragon’s cynicism haunts him day and night.

At the end, of course, the brawny hero Beowulf shows up. But in Gardner’s retelling, Beowulf is no stupid, muscle-bound hero. He is Grendel’s superior not just in physical strength but in philosophical prowess, a man who has come through the fires of nihilism himself. As he fights Grendel physically, he also whispers into his ears unwelcome truths. The stories we tell ourselves matter. What we believe changes the world because it changes our choices. It determines how we live and how we die. Then Beowulf rips Grendel’s arm off.

Grendel dies skeptical and angry – giving the world the finger in his last moments. It’s too late and too hard for him to change. But the novel about Grendel shows us in Beowulf a peculiar, difficult, but powerful alternative to nihilism – a heroic existentialism that reminds me of the philosophy of Camus.

There are other ways of resolving the threat of nihilism, of course. Some of my students eventually make their way to spiritual practices or religious communities. Others – as Carol Gilligan suggests that many women do – evolve a moral practice that involves making decisions in terms of networks of care and connection. Still others, I suspect, are muddling through life with no rationally worked-out moral code but with good hearts. (And they’ve learned at the school one key bit of knowledge: that a good life doesn’t happen by accident. It’s built, by hard emotional work on a foundation of earned self-respect.)

That’s one form this moral crisis takes in bright teenagers. But what about us, in the later stages of our lives? How are we going to joust with nihilism and despair? Share your thoughts! I’ll be interested to hear them….

So wonderful, and helpful. Yes, these dark moments, or sometimes more than just moments, creep in regularly. For me, Gilligan’s “networks of care of connection” (especially the connection with a unique, loving friend) and the beauty of the natural world, can usually, though not always, help to fence out despair. As you now know (since we tracked it down together!), the name of the writer you were trying to remember is William Carlos Williams, and the poem is “The Last Words of My English Grandmother” (“Trees? Well, I’m tired/ of them and rolled her head away.”) XXX . . .

I read your post on nihilism this evening, after I got home from a chamber music concert in which a trio of musicians on flute, clarinet and piano combined to produce some of the most interesting and emotionally touching sounds I have ever heard. They were so high caliber that two of them play with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. The sound they shared with the audience can’t be evoked with words. It would take hearing the sound. But let me try to describe other aspects of the experience and explain why it has something to say in response to your question.

The setting was a small, dark room in the basement of a restaurant. There is a full bar along the back wall of the room. A grand piano, some mic stands, and spotlights on the performers are along the wall opposite the bar. In between the room is packed with small round tables with chairs around them, facing toward the performers. The chairs are filled.

Here is the tension that defines the night. The bar was open and waitresses kept filling orders throughout the performance. Glasses are clinking, ice is being shot into glasses, dirty dishes get put into a sink, the blender revs, and several times trays of dishes are dropped and breaking ceramic sounds burst out like mortar rounds. The bartender makes no effort to mute his activities.

Sublime jazz sounds from the clarinet blend with a luscious flute. The two musicians are brothers and they have been playing together for so long it’s like each of them is one leg and together they make one walking human being. Inseparable, yet each one’s solos amaze the listener. Sometimes the third musician on the piano complements the texture of the brothers’ sound.

But there is a fourth musician. The bartender. The four sounds fill the space. Percussion from the bar while the clarinet plays a tango. And the last piece includes poetry by Langston Hughes read soulfully by a man from Chicago in a suit and a 1940’s hat. Poems about bar fights in a bar where the musicians are fighting off the competition from the bartender.

If the musicians performed in a theater with no other sounds, would it have been the same experience? The Battle of Midway with only one side’s guns? I was angry about the bar sounds at the time, but as I write this and think about your nihilism issue, the contrapuntal effect of it all seems relevant.

Maybe life is made richer by the battle of working to achieve the sublime in the midst of chaos—until you are in the ambulance and you are tired of seeing the trees. i understand that feeling. But then I have some new experience that provides just enough happiness or pleasure to make me push on. The prospect of you and I taking in the beauty of Biltmore. Debbie saying something funny, yet practical. My old dog Chester giving me a loving look and scolding me by whining when I stop scratching behind his ears, so I feel loved and go back to touching him.

So that’s my method of coping with frustration, boredom, fatigue, despair. Find a little tidbit of connection to a person or a creature, to an experience, to a battle where I can fight against the chaos from the bartender, to wonder why Bernie Sanders keeps gumming up the work of getting rid of Trump, to observe that Elizabeth Warren’s first response to a question about how it feels to see her name on the ballot for President is to say, “I made it out of Oklahoma,” and think of my splendid friend Nancy and know she feels the same way. Then Elizabeth said it made her miss her parents because they would be so proud of her. And that made me miss my Dad. And then Lawrence O’Donnell said it made him miss his parents.

So we all have big accomplishments and tiny ones and loving connections and longings for pleasures and painful memories. And nihilism and despair. And people who care about us. And the knowledge that those who care about us would be hurt if we give up. That’s kept me going when I have wanted to quit. Knowing I am loved and needed.

That’s my 2 cents, tonight anyway.

Wow, what a BEAUTIFUL response! I loved the description of the music and the bar-tender. I would have been annoyed, too, and yet you’re right: it may have been a richer experience in the end because it was in an environment that was alive with people making drinks, getting drinks, and moving around. And it’s CERTAINLY true that contact with the people we love makes a big difference when we’re feeling down. Sometimes all it takes for me is to see a cute kid or dog!