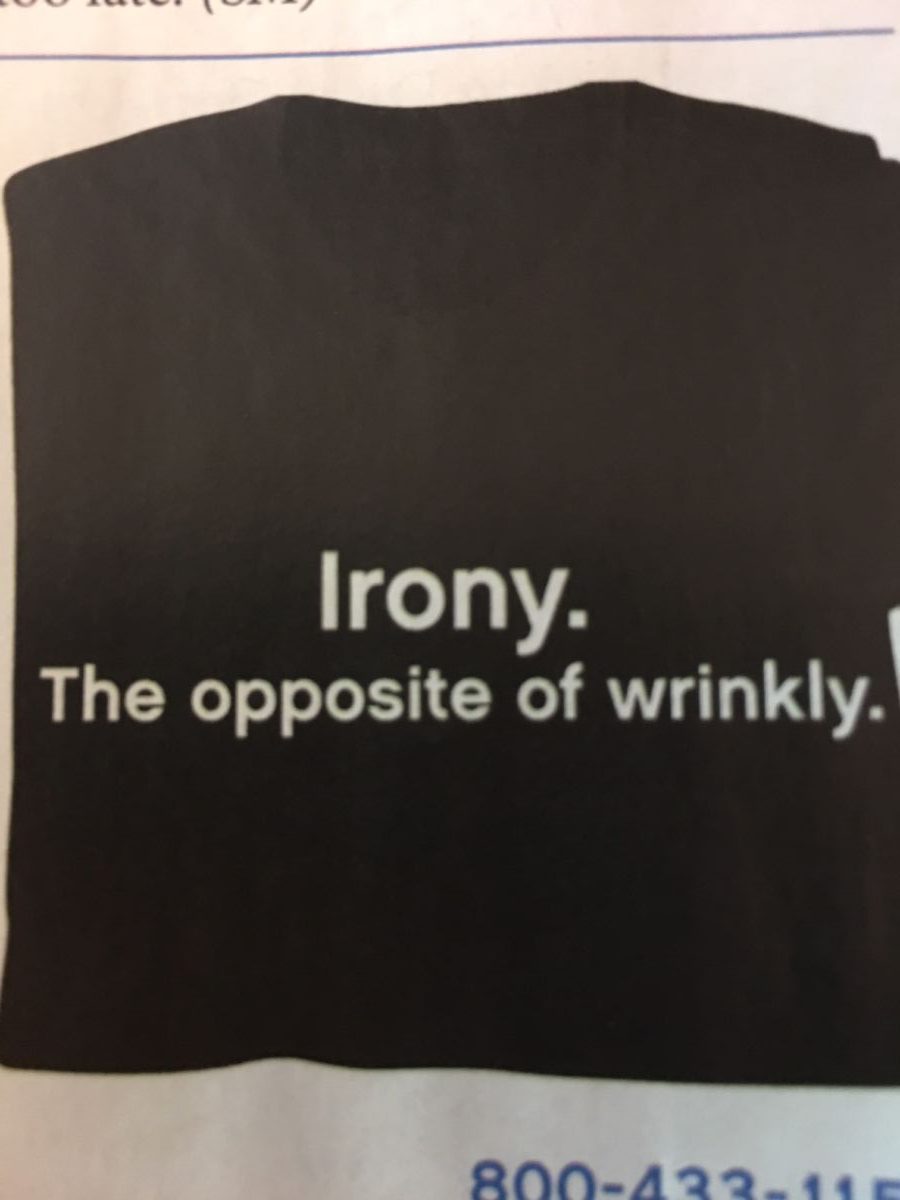

Here’s a great epigram I saw recently on a tee-shirt:

Irony

The opposite of wrinkly.

(If you desperately need it for yourself or a friend, it’s from the Bas Bleu catalog.)

In my online class on The Tempest last week, the teacher talked about how, for Shakespeare, snarky wordplay is a sign of Machiavellian bad guys. It’s not an infallible rule even in Shakespeare: think of Prince Hal bandying words with Falstaff in Henry IV, Part One (perhaps he’s a Machiavellian good guy?) or Benedict and Beatrice sniping at each other in Much Ado About Nothing (though one can’t help but hope they’ll be less hard on each other when they’re married). But yes, cynical puns do salt the language of Shakespearean villains like Richard III, Edmund (in King Lear), and Iago.

That’s not how we typically think about snark now.

These days, in popular satirical series—South Park, Parks and Rec, The Office, House of Cards, Vampire Diaries—snark is the dominant flavor. (A bit of sweetness gets tossed in from time to time, for balance.) For us today, snark has become a sign of a canny intelligence. We like our protagonists cynical, sarcastic, and slightly depressed. We enjoy watching them operate on the sidelines or manipulate the system to get what they want. Earnestness can feel so midwestern nowadays, so old-fashioned and naïve.

Because I happen to be midwestern and old-fashioned, I prefer my snark as the two drops of tabasco or sriracha that spice up a dish—or dialogue. It adds pepper, humor, and a little bite; a sarcastic edge keeps the action from being too bland. And it’s useful as well as funny: In real life, it keeps us from getting taken in by the manipulations of politicians or advertisements. But it’s also true that sarcasm an sneering, however clever, are essentially derivative: they feed off, and sometimes even destroy, positive impulses. As a habitual attitude, they encourage passivity.

Snark is only one form of irony, of course. Irony includes any use of words in which the intended meaning is essentially the opposite of what is said literally. One of my professors in graduate school told a wonderful story about a conference on rhetoric in which a presenter commented in passing on how odd it was that double negatives often make a positive (“He was not without his charms”), while double positives usually amplify each other (“I was totally and completely overwhelmed”) and never create a negative. Then from the back came a jaundiced voice, “Yeah, yeah.” (So double positives can make a negative!)

In The Tempest, two of the richest and most moving moments of the play echo with gentler forms of irony. In the final act, Prospero has commanded his airy spirit, Ariel, to corral the people who betrayed him in one location and hold them captive with magic. After twelve years of brooding on his wrongs, Prospero can finally take his revenge on the people who put him out to sea with his daughter. Ariel reports that his enemies are gathered in a circle and spellbound.

ARIEL

. . . Your charm so strongly works ‘em,

That if you beheld them, your affections

Would become tender.

PROSPERO Dost though think so, spirit?

ARIEL Mine would, sir, were I human.

PROSPERO And mine shall.

Prospero chooses his “nobler reason” against his thirst for vengeance. How ironic and moving it is to watch Ariel, “which art but air,” gently remind Prospero how to be his best human self.

Another beautiful moment of the play’s conclusion involves s a different kind of irony: dramatic irony, in which the audience knows more than the character who is speaking. When Prospero reveals the newly engaged Ferdinand and Miranda, his fifteen-year-ld daughter sees other human beings for the first time. (They are, of course, the bad guys whom Prospero’s storm has shipwrecked on their island.) Miranda famously marvels,

O wonder!

How many goodly creatures there are here!

How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world

That hath such people in it!

Then, with world-weary wisdom, Prospero quietly says, “Tis new to thee.”

Here we see the joyfulness of innocence juxtaposed with the sensible suspicion required for adult life, the dark strain of tragedy (now past and survived) brightened by the festive note of comedy. It’s a rich, beautiful mix, fitting for the final notes of Shakespeare’s last complete play. It’s fitting, too, for all those of us in the later stages of life, who are watching children and grandchildren, nieces and nephews, embarking on the great human journey. With tender, hopeful hearts, we watch as they launch into the big, complex world that we know will break their hearts and then mend them over and over again—hoping that they, and we, can come through the world’s storms safely and become our best human selves.

Such a great reminder. Sometimes we seem to fear being viewed as naive so much that we fall back into reflexive cynicism as protection. Yet, ingenuous delight can often be the central ingredient of real joy. When we lose that capacity the world can go very dark indeed.